Stop Following Sameness.

We’re all capable of being different. We just have to learn to swivel our hips and stop trying to be someone else.

“I never copied anybody.” Elvis Presley

“I don’t know exactly what those women are screaming at,” Elvis Presley once told a reporter. “I just try to be myself.” As humble as that sounds, Elvis knew he could only stand out from other artists if he was different. He wasn’t looking for affectation, he was looking for him.

Every artist knows that, but only a few know how to be different. On one hand, it takes courage, on the other, it takes humility. Humility is knowing what you are, and accepting what you’re not.

A few years back, Eric Clapton was part of a benefit for the late George Harrison. Clapton took the stage with a number of artists, including Prince. At the conclusion of the show, Prince played an outstanding lead on “While My Guitar Gently Weeps.” Coming off the stage, someone asked Clapton how it felt to be the world’s greatest guitarist. “I don’t know,” he replied, “ask Prince.”

Paying Prince the compliment was like saying, “We’ve both found our place in music. We’ve both found ourselves.”

Here’s what Clapton was really saying: “We all have our moments. Prince had his.” Clapton knew it was Prince’s moment and acknowledged it as such. That didn’t take away from Clapton’s talent. He was comfortable with his difference and willing to recognize Prince’s at the same time.

His path and Prince’s path were unique in their own way. Paying Prince the ultimate compliment was like saying, “We’ve both found our place in music. We’ve both found ourselves.”

Like all great artists — or anyone unique — there are always two paths to choose. One is to be like everybody else. The other is — don’t.

We don’t trust our singing talent, for one thing. Nor do we imagine swivelling our hips will get us anything but arrested.

That’s not easy to do. We’re not all artists or musicians like Elvis or Eric Clapton. If anything, we’re brought up to be accepted. Schools teach sameness, society expects us to follow rules, our family wants to be proud.

Given that environment, nobody expects us to step out of the ordinary. In some respects, it’s counterproductive. Even Elvis admitted he wasn’t trying to be a rebel. Rebellion doesn’t pay the bills. But he also new being ordinary didn’t pay the bills, either. There had to be something in between. Elvis found it by swivelling his hips. It ended up paying a lot of bills.

We can admire someone like Elvis Presley. That doesn’t mean we’d ever follow a similar path. We don’t trust our singing talent, for one thing. Nor do we imagine swivelling our hips will get us anything but arrested.

That said, if we look back at our lives, we can see where we could have been different. According to scientists, it’s in all of us. We all have unique genes that make us particularly good at something.

In public school, the principal told my parents I should quit and learn something like small engine repair.

It’s a matter of realizing we’re not going to get recognized — or be anything — if we don’t do something unorthodox.

Back in the 60s, I wasn’t a good student. In public school, the principal told my parents I should quit and learn something like small engine repair.

Maybe he felt guilty afterwards. He decided to let me join the school dance committee. There was no money, so I wrote to all the soft drink companies. I did the same with the grocery stores. Four days later, ten cases of soft drinks, twenty packages of hot dogs and the equivalent number of buns were delivered to my house. I also supplied the band for the dance (me playing guitar—albeit badly).

Nothing I’ve ever done was successful when I tried being like everyone else.

In high school, I had one of the lowest CAAT scores. After graduation, with no hope of getting into a university, I took a year off, worked in factories, loaded trucks, then became assistant manager of a shoe store.

When the manager left at five o’clock, I brought out a stereo, turned up the music (disco), and told my staff to have fun. We had the best three-month sales figures of our franchise.

I can’t say that I was trying to be different. All I knew was I couldn’t approach things normally. It didn’t work. Nothing I’ve ever done was successful when I tried being like everyone else.

Let’s take a look at someone like Richard Branson. He’s done amazing things. So why aren’t we trying to be like him? Why do we watch movies filled with underdogs? Why do we live vicariously through others?

How often do we fall back to “normal,” saying: “I’ve got my family to think about, the mortgage, the payments on the car”? How many of us have built a wall of responsibility, justifying why we can’t — or won’t — move outside our comfort zones?

In Dr. Seuss’s “Oh, The Places You’ll Go,” he writes: “You have brains in your head, you have feet in your shoes, you can steer yourself any direction you choose.” He extols confidence, saying: “You’re the best of the best,” something parents have taken to heart. They tell their children the same thing, echoing Seuss’s last words: “KID, YOU’LL MOVE MOUNTAINS!”

To quote Richard Branson: “You have to fight tremendous resistance.” That can’t be done with optimism (silly or not).

We tell young people they can “MOVE MOUNTAINS,” forgetting that it takes more than optimism or even a massive crane.

To quote Richard Branson: “You have to fight tremendous resistance.” That can’t be done with optimism or machinery. It takes a great deal of originality and, above all, guts.

When I was selling shoes, we were in the midst of a recession. Consumer confidence was low. Stores around me had sales galore. We stayed away from flat 20% off specials. It showed desperation. We turned up the music. Our sales grew right through January, what the Merchant’s Association called “A disastrous month for the retail industry.”

I hear people talk about how “everyone’s opinion should be worth the same.” All this does is produce sameness. In a room of ten people, 90% are going to be normal. They expect that of themselves. They follow party line.

We place a lot of emphasis on “normal” yet, by it’s very definition, “normal” doesn’t allow for expansion.

Get out there in your minivans with your 2.5 kids and designer dog, and raise awareness for the average! Be an advocate for your own, wonderfully middling life.

Look at the definition of “normal”: “Conforming to a standard; usual, typical or expected. Synonyms: usual, standard, ordinary, customary, conventional, accustomed, expected, wanted.”

One woman, named Caitlin, wrote in her blog/post: “I am an advocate for average. Average is wonderful; a cause worthy of advocacy…Get out there in your minivans with your 2.5 kids and designer dog, and raise awareness for the average! Be an advocate for your own, wonderfully middling life. Speak out for women in the middle everywhere! We are average and we’re happy!”

Caitlin — and many others — may be happy with “average,” but it’s hard to imagine them telling their children, “KID, YOU’LL MOVE MOUNTAINS!” It’s also hard to explain to people like Caitlin that “average” is getting us nowhere in this world. Two back-to-back recessions should convince us of that.

If we accept normalcy, we’ll never find ourselves.

If we’re not teaching guts and non-standardized thinking, we’re not moving mountains, we’re waiting for someone else to do it. We’re on the sidelines, offering a cheering section to whomever does move mountains. But it won’t be us. Or our children. Or our children’s children.

If we accept normalcy, we’ll never find ourselves. You have to think more like Elvis. You have to imagine standing on the doorstep of Sun Records with hundreds of other unknown artists. Did Elvis expect to be recognized based on his own merits? That wasn’t Elvis. He knew it took much more than that.

He decided to move mountains, just like Eric Clapton and Prince and Richard Branson. It’s not someone saying, “KID, YOU’LL MOVE MOUNTAINS!,” it’s you convincing yourself those mountains can be moved.

It takes work, it takes the willingness to try. Like those scientists said, it’s in all of us to be different. If that’s what we want.

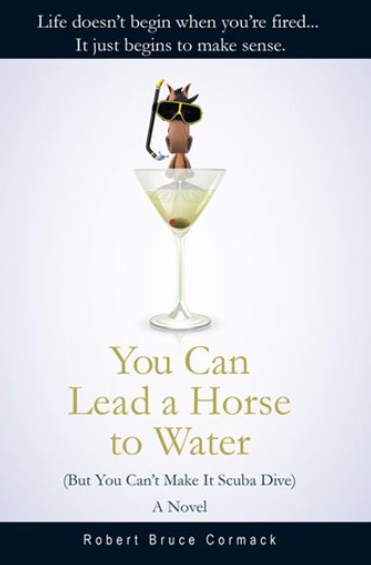

Robert Cormack is a freelance copywriter, novelist and blogger. His first novel “You Can Lead a Horse to Water (But You Can’t Make It Scuba Dive)” is available online and at most major bookstores (now in paperback). For more details, go to Yucca Publishing or Skyhorse Press.